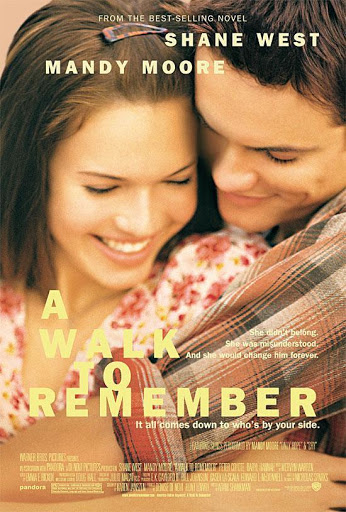

The story of two North Carolina teens, Landon Carter and Jamie Sullivan, who are thrown together after Landon gets into trouble and is made to do community service.

Directed by: Adam Shankman

Screenplay by: Karen Janszen

Starring: Shane West, Mandy Moore, Peter Coyote, Daryl Hannah

“A Walk to Remember” is a love story so sweet, sincere and positive that it sneaks past the defenses built up in this age of irony. It tells the story of a romance between two 18-year-olds that is summarized when the boy tells the girl’s doubtful father: “Jamie has faith in me. She makes me want to be different. Better.” After all of the vulgar crudities of the typical modern teenage movie, here is one that looks closely, pays attention, sees that not all teenagers are as cretinous as Hollywood portrays them.

The singer Mandy Moore, a natural beauty in both face and manner, stars as Jamie Sullivan, an outsider at school who is laughed at because she stands apart, has values, and always wears the same ratty blue sweater. Her father (Peter Coyote) is a local minister. Shane West plays Landon Carter, a senior boy who hangs with the popular crowd but is shaken when a stupid dare goes wrong and one of his friends is paralyzed in a diving accident. He dates a popular girl and joins in the laughter against Jamie. Then, as punishment for the prank, he is ordered by the principal to join the drama club: “You need to meet some new people.” Jamie’s in the club. He begins to notice her in a new way. He asks her to help him rehearse for a role in a play. She treats him with level honesty. She isn’t one of those losers who skulks around feeling put upon; her self-esteem stands apart from the opinion of her peers. She’s a smart, nice girl, a reminder that one of the pleasures of the movies is to meet good people.

The plot has revelations that I will not reveal. Enough to focus on the way Jamie’s serene example makes Landon into a nicer person–encourages him to become more sincere and serious, to win her where she approaches him while he’s with his old friends and says, “See you tonight,” and he says, “In your dreams.” When he turns up at her house, she is hurt and angry, and his excuses sound lame even to him.

The movie walks a fine line with the Peter Coyote character, whose church Landon attends. Movies have a way of stereotyping reactionary Bible-thumpers who are hostile to teen romance. There is a little of that here; Jamie is forbidden to date, for example, although there’s more behind his decision than knee-jerk strictness. But when Landon goes to the Rev. Sullivan and asks him to have faith in him, the minister listens with an open mind.

Yes, the movie is corny at times. But corniness is all right at times. I forgave the movie its broad emotion because it earned it. It lays things on a little thick at the end, but by then it had paid its way. Director Adam Shankman and his writer, Karen Janszen, working from the novel by Nicholas Sparks, have an unforced trust in the material that redeems, even justifies the broad strokes. They go wrong only three times: (1) The subplot involving the paralyzed boy should have either been dealt with, or dropped; (2) It’s tiresome to make the black teenager use “brother” in every sentence, as if he is not their peer but was ported in from another world; (3) As Kuleshov proved more than 80 years ago in a famous experiment, when an audience sees an impassive closeup, it supplies the necessary emotion from the context. It can be fatal for an actor to try to “act” in a closeup, and Landon’s little smile at the end is a distraction at a crucial moment.

Those are small flaws in a touching movie. The performances by Moore and West are so quietly convincing we’re reminded that many teenagers in movies seem to think like 30-year-old standup comics. That Jamie and Landon base their romance on values and respect will blindside some viewers of the film, especially since the first five or 10 minutes seem to be headed down a familiar teenage movie trail. “A Walk to Remember” is a small treasure.

Taken from Roger Ebert